Medications

Various medications have been explored for the management of hyperacusis, noxacusis, middle ear myoclonus (MEM), and tonic tensor tympani syndrome (TTTS), though none have demonstrated consistent benefits.

Some patients report temporary relief with benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam or diazepam, which can help calm neural hyperexcitability and reduce anxiety associated with sound sensitivity. However, due to their high potential for dependence and withdrawal, benzodiazepines should generally be avoided, with limited use reserved for specific circumstances such as travel. Prolonged benzodiazepine use may exacerbate hyperacusis and tinnitus symptoms due to interdose withdrawal effects associated with dysregulation of the glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems.

Other medications, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and anticonvulsants have been used with variable results.

Most antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, and tricyclics) work by increasing serotonin signaling, typically by blocking its reuptake so more of the neurotransmitter remains active in the synapse. With long-term use, the brain adapts to this heightened serotonin activity by adjusting receptor sensitivity and neurotransmitter balance. When the medication is reduced or stopped, serotonin function can temporarily fall below normal, leading to a withdrawal phase sometimes called antidepressant discontinuation syndrome (ADS). During this period, people may experience symptoms such as anxiety, low mood, irritability, dizziness, “brain zaps,” and sleep disturbances as the serotonin system gradually re-stabilizes. To minimize these effects, antidepressants are usually tapered gradually under medical supervision rather than stopped abruptly.

Ambroxol is a mucolytic drug with sodium channel–blocking and neuroprotective properties. Some patients report that it reduces pain, but when effective the relief is usually mild, and for some patients it has no effect at all.

Overall, pharmacologic treatments remain largely experimental, should be individualized for each patient, and used in conjunction with a controlled sound environment to minimize further auditory injury.

Real-world data collected from patients who have tried various treatments including antidepressants, ambroxol, Botox, and tympanic membrane paper patching can be found in this spreadsheet.

Summary of Medications

- Benzodiazepines (clonazepam, diazepam): May temporarily reduce sound sensitivity, muscle spasms, and anxiety but carry an extremely high risk of dependence and withdrawal.

- Withdrawal from benzodiazepines can be extremely difficult, often requiring a gradual taper over many months. In some cases, individuals experience protracted withdrawals that may persist for years, underscoring the need for great caution when using or discontinuing these medications.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (clomipramine, amitriptyline, nortriptyline): Appear to provide greater symptom relief for individuals with sound sensitivity related to neuropathic pain (neuralgia) than for those with primary loudness hyperacusis.

- SNRIs (duloxetine): Explored for central pain modulation, variable effectiveness.

- Anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin): May help neuropathic auditory pain, variable effectiveness.

- Ambroxol: Experimental use for neuroprotection and auditory pain relief, variable effectiveness. Ambroxol is generally considered the safest of the medications listed here, with the most common side effects being gastrointestinal issues and dryness of the mouth and throat. Ambroxol is not sold in the United States, but it can be purchased from overseas without a prescription and shipped to the U.S.

Clomipramine

Clomipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), warrants special mention as it has become the most widely used medication for managing symptoms of hyperacusis and sound sensitivity associated with neuralgia. Among the various pharmacologic options explored, clomipramine has shown the most consistent anecdotal benefit in reducing auditory hypersensitivity, pain, and related anxiety.

Despite reports of success from many patients, a significant number experienced little to no improvement in their symptoms while using clomipramine. At Hyperacusis Guide, we believe we have identified a specific subgroup that responds most favorably to clomipramine. These patients typically share the following characteristics:

- Hyperacusis symptoms are mild or absent: Patients are able to carry out normal daily activities, can usually continue working a quiet job, and can tolerate normal environmental sounds without fear of a permanent setback, though some require the use of hearing protection. Aural fullness is generally mild or absent in these individuals.

- Based on our knowledge, no patients who are truly severe and homebound have reported meaningful improvement in their symptoms after taking clomipramine.

- No permanent setbacks: Patients may have a temporary setback from exposing to sound above their tolerance threshold, but return to their previous baseline after a period of rest.

- Neuropathic pain (neuralgia): Almost all of these patients complain of pain that would be most consistent with neuralgia, frequently a burning sensation that radiates from around the ear into the face and head. Primary loudness hyperacusis patients usually complain of more focused pain that localizes to the middle ear (deep to the tympanic membrane).

Clomipramine belongs to an older class of antidepressants known as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Although effective for certain conditions, TCAs affect multiple neurotransmitter systems and are associated with a wide range of side effects. Clomipramine has additionally been reported to worsen symptoms of visual snow syndrome (VSS), potentially intensifying visual disturbances like static-like visual noise, light sensitivity, and after-images in susceptible individuals.

Several individuals have reported an initial increase in tinnitus after starting clomipramine, occasionally presenting as musical tinnitus. In many cases, this exacerbation was temporary, with tinnitus gradually returning to baseline after a few weeks of continued use. However, some patients were unable to tolerate the medication and discontinued treatment due to a sustained worsening of tinnitus.

Although clomipramine is typically introduced at a low dose, it often must be titrated to doses exceeding 200 mg per day before any meaningful improvement in symptoms is observed, which increases the likelihood of adverse effects.

Some patients have reported fewer side effects and less pronounced changes in tinnitus when using the sustained-release (SR) formulation of clomipramine. The original version of clomipramine is available in the United States, but the sustained-release version is not and must either be purchased from an international pharmacy or prepared at a compounding pharmacy, which are available in most states.

Please refer to the spreadsheet which provides numerous patient reports on clomipramine use, including information on dosage, effectiveness, and side effects. **In regard to clomipramine, the findings in the spreadsheet should be interpreted with caution because the data does not reflect direct user input and is relayed through several individuals responsible for maintaining the spreadsheet, potentially biasing the results in favor of clomipramine.**

Botox

Botox (botulinum toxin type A) has been studied as a potential treatment for hyperacusis, noxacusis, middle ear myoclonus (MEM), and tonic tensor tympani syndrome (TTTS) because of its ability to temporarily weaken overactive muscles that may contribute to sound sensitivity and pain.

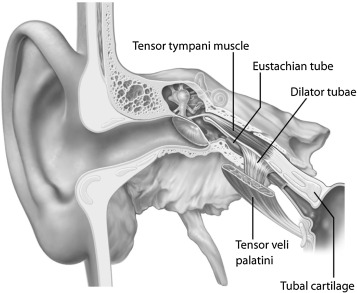

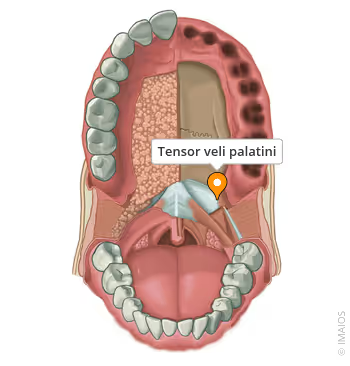

In cases of MEM or TTTS, conditions characterized by involuntary contractions of the tensor tympani or stapedius muscles, Botox injections have been used to reduce muscle spasms and relieve the associated fluttering, thumping, or pressure sensations in the ear. TTTS often coexists with hyperacusis and noxacusis, so the benefit of Botox in some of these cases may stem from its ability to relax the tensor tympani muscle.

The toxin is most commonly injected into the tensor veli palatini (TVP) muscle which is closely related to the tensor tympani muscle through a shared tendinous attachement. The TVP tenses the soft palate and opens the Eustachian tube, helping to equalize pressure in the middle ear. In rare cases, the toxin is directly injected into the tensor tympani and stapedius muscles using a transcanal approach (through the tympanic membrane) under endoscopic guidance.

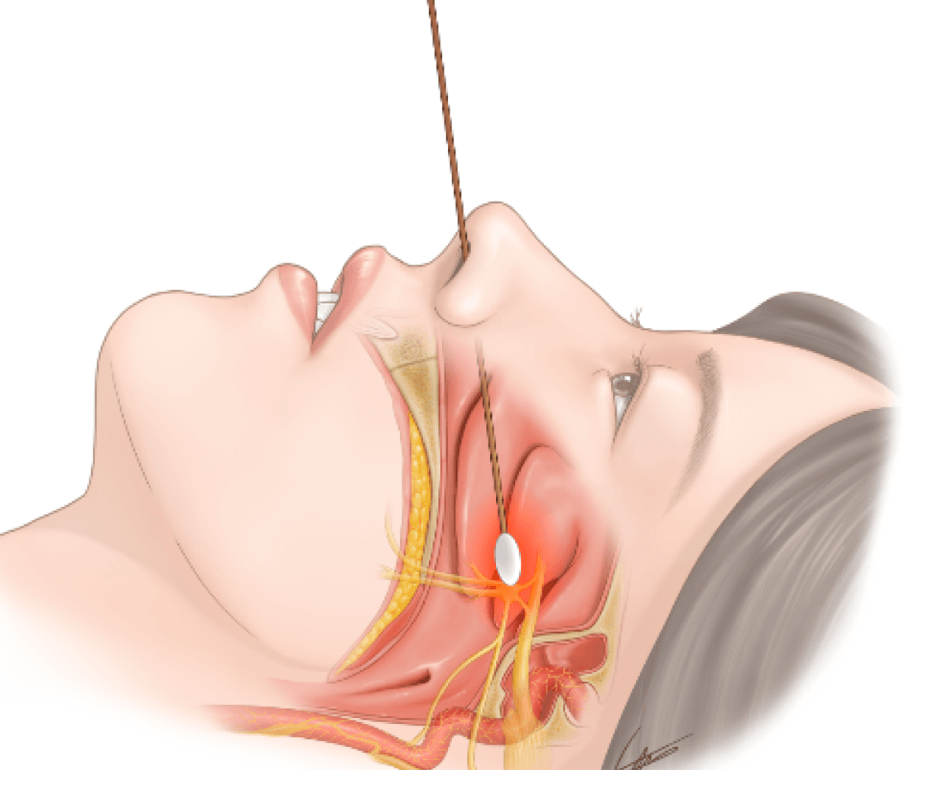

The video below demonstrates injection of Botox into the tensor veli palatini (TVP) using a transnasal endoscopic approach. You will notice the needle tip within the TVP muscle near the lower-left edge of the field of view. The physician who perfomed this procedure provided a brief description of his technique:

- Inject 10–15 U of Xeomin or Botox, using nasal endoscopic approach, using 1 ml syringe and lumbar puncture needle (26 G) directly into the muscle body of the tensor/elevator tympani, a few millimeters behind the inferior turbinate.

- Observe a swelling of the muscle when injecting.

- Effects start about 2–3 days after the injection. We discussed the risks/potential side effects of a Botox injection into the palate including velopharyngeal insufficiency, nasal reflux, and hypernasal speech.

In some reported cases, patients have experienced a significant reduction in middle ear spasms, sound sensitivity, and pain following Botox treatment, with effects often lasting several months. However, other patients have reported little to no benefit. The available evidence is limited to a small number of case reports and pilot studies, and outcomes vary widely depending on injection technique and the underlying cause of the patient’s symptoms. Consequently, Botox treatment for hyperacusis, MEM, and TTTS is considered experimental.

Please refer to the spreadsheet for detailed reports from patients treated with TVP Botox, including the number of units administered, effectiveness, and side effects.

Sphenopalatine Ganglion (SPG) Block

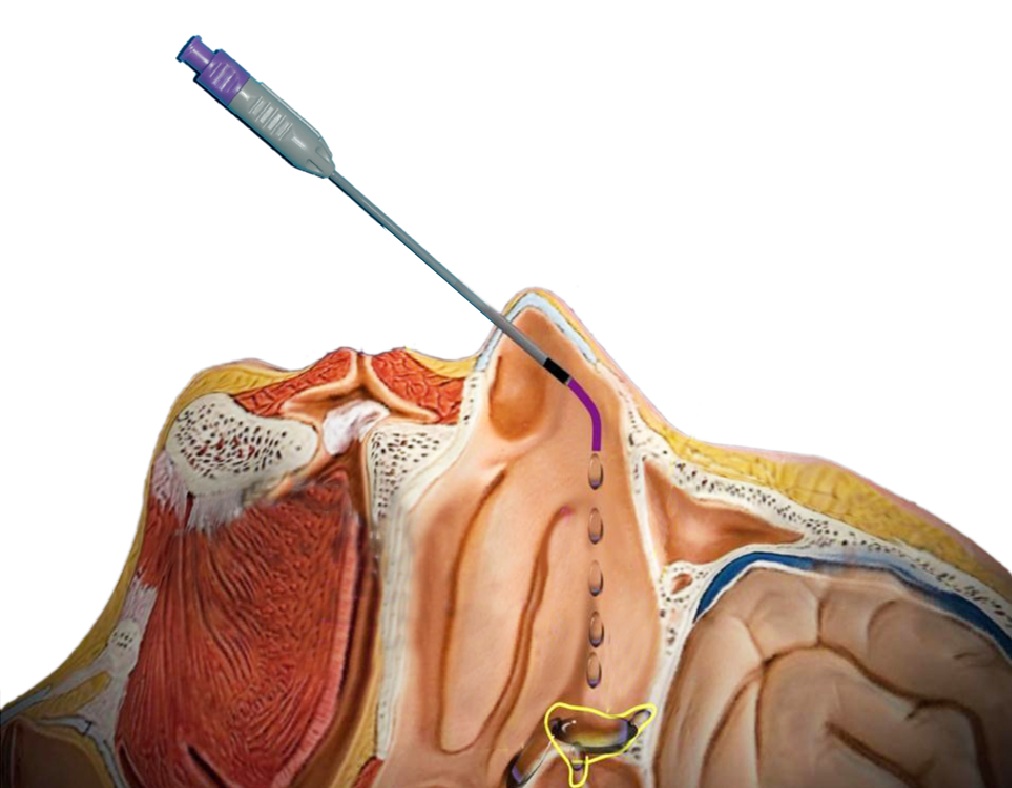

A sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) block is a minimally invasive procedure in which local anesthetia or steroids are delivered to the sphenopalatine ganglion (a parasympathetic nerve bundle located behind the nasal cavity) to interrupt pain signaling. The block may be performed using a soft transnasal applicator (cotton swab) saturated with anesthetic, a catheter-based delivery system (syringe attached to a thin catheter that is guided through the nasal cavity), or in some cases a needle introduced under endoscopic or fluoroscopic guidance.

Most commonly, clinicians use a local anesthetic such as lidocaine or the longer-acting bupivacaine. The procedure has traditionally been used for migraine and facial pain, but it has more recently been explored as a potential treatment for hyperacusis and noxacusis because of its ability to reduce trigeminal activity, middle ear muscle tension, and sound-induced neuropathic pain.

In some practices, a corticosteroid (such as triamcinolone or dexamethasone) is added to the anesthetic to extend the therapeutic effect. While steroids do not produce a true long-term nerve block like radiofrequency ablation, they may prolong symptom relief beyond the duration of local anesthesia alone, which typically lasts only a few hours. Evidence for SPG blocks in hyperacusis and noxacusis remains limited, but some patients report short-term reductions in auditory pain and improved sound tolerance following the procedure.

The video below demonstrates a technique for accessing the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) using a needle under fluoroscopic guidance. The SPG can also be accessed with a needle using a transnasal endoscopic approach (not shown).

The key advantage of using a needle is the ability to deliver local anesthetia or steroids directly into the SPG and surrounding tissues, whereas the cotton swab and catheter methods (shown below) apply local anesthesia to the mucosa overlying the SPG and rely on passive diffusion.